The IMF and World Bank have both recently raised the issue of support to the state sector inhibiting private sector growth

- In its December review of Egypt’s standby agreement, the IMF stated that economic development required the removal of bureaucratic obstacles to the private sector

- Soon after, a World Bank report raised concerns about privileged treatment of the State impeding private sector growth

- The IMF and World Bank also acknowledged Egypt’s deft handling of the coronavirus crisis in 2020 and the positive impact on investor confidence of the economic reform programme in 2016-19

- Nonetheless, enabling the private sector to move up the value chain remains the key to future job creation, poverty reduction and maintaining long-term financial stability

IMF & World Bank highlight private sector as key to development

On December 18, the IMF completed the first review of a 12-month Stand-By Agreement (SBA), signed in June to bolster Egypt’s ability to contain the fallout of the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic on public health and the economy. The completion of the review triggered the release of a second tranche of $1.7bn from the $5.2bn SBA, bringing total disbursements to just over $3.6bn.

An IMF statement on the outcome of its review was generally positive, noting that the authorities’ response, which included a $6bn fiscal stimulus package (equivalent to about 1.2% of GDP) and cumulative cuts to the benchmark interest rate of 400 basis points, meant that the pandemic’s impact on the economy was “less severe than expected”.

However, the IMF emphasised that a sustained recovery and long-term job creation would require “ensuring a level playing field for all economic agents and removing bureaucratic obstacles to private sector development”.

A World Bank (WB) Group report (Creating Markets in Egypt: Country Private Sector Diagnostic), published days after the IMF’s completion of its review, raises similar concerns around the “growing and privileged role of the State in economic activities” as a key impediment to private sector-led growth.

The WB report provides an excellent deep dive into the structural reasons for Egypt’s low non-extractives private and foreign investment, which remains a key hindrance to employment creation. The report details issues ranging from a protectionist trade policy regime to non-tariff measures that constrain the export-competitiveness of private firms, undercutting the potential of exports as a key source of foreign-currency earnings.

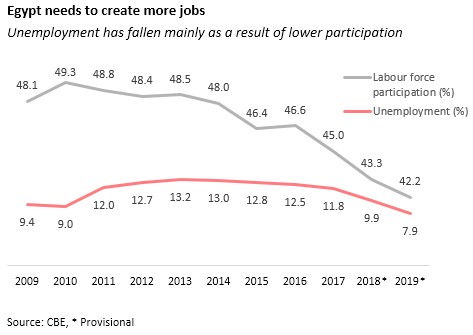

Given their political sensitivity and inflationary impact, a currency devaluation and subsidy rationalisation measures have been the headline-grabbing features of Egypt’s 2016-2019 economic reform program. The macroeconomic stabilisation that resulted has restored investor confidence – reflected in sizable foreign holdings of domestic debt – but has not translated into significant employment creation or a marked pick-up in foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows. To translate Egypt’s hard-won macroeconomic stability into robust jobs growth, poverty reduction and stronger financial buffers, which would help Egypt transition from a lower to an upper-middle income country, the next phase of Egypt’s reform drive must focus on enabling the private sector to move up the value chain.

State-led development

Egypt’s strategy of state-led development – a legacy of the post-colonial era – has been reinforced in recent years by state-led implementation of grand national projects. For instance, two of the signature projects of the Sisi era that have been touted as transformative for the economy – the expansion of the Suez Canal Development Zone and a New Administrative Capital (NAC) – are being implemented by state-led consortiums. Egypt’s sprawling public enterprise sector consists of 297 state-owned enterprises (SOEs), 51 economic authorities (EAs), and 60 companies affiliated with the Ministry of Defence. The economic size of the public sector in Egypt was estimated by the IMF at 31% of the total economy in 2017, about 2‒3 times the average in leading emerging economies. In addition, employment in the public sector currently exceeds 6 million people (excluding the armed forces of nearly 1.5 million), or more than 22% of the country’s labour force, in contrast with around 13% in Turkey and less than 9% in South Korea.

Protectionism hampers the external sector

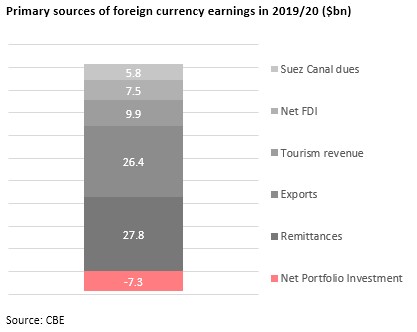

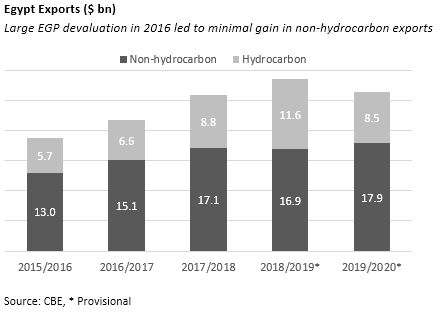

Despite a recent recovery in official reserves (they are currently equivalent to more than six months of imports), Egypt’s high and rising debt-servicing burden and import-dependency require greater foreign currency earnings. Egypt’s main sources of hard currency – Suez Canal dues, remittances from Egyptians working abroad and tourism – have all been vulnerable to global lockdowns and the contraction in global trade associated with the pandemic. Egypt could strengthen its long-term reserves position by improving the export-competitiveness of public and private firms and attracting greater FDI inflows. Only 1.1% of the firms surveyed for the abovementioned WB study export, while only 9% of manufacturing firms export directly. Currently, exports are mainly centred on primary commodities and less sophisticated products with limited potential for technology transfer and participation in global value chains.

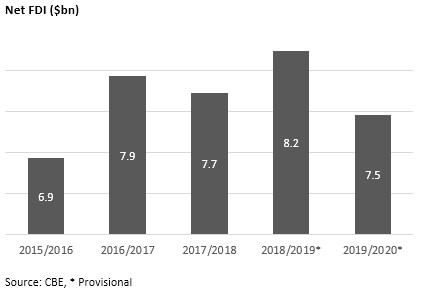

In addition, FDI inflows to Egypt, while the largest in Africa, remain low and are declining. In FY2019, FDI reached 2.7% of GDP, well below its share in the 2000s. FDI also remains concentrated in the petroleum sector (74.3% of total FDI), which has fewer opportunities for job creation, given its capital-intensive nature. Conversely, the share of FDI in more labour-intensive sectors, such as services, manufacturing, and construction, remained modest at 14%, 5%, and 2%, respectively.

Therefore, Egypt needs a wider, diversified and more competitive export base along with higher value-added products to mitigate foreign currency risks. Egypt’s export performance has been hampered by a highly protectionist trade regime, including high and sometimes unpredictable import tariffs on items ranging from food products to manufacturing inputs. According to the WB Country Private Sector Diagnostic, this makes Egypt the second-most-protected economy in the world after Sudan and “reduces the overall incentive to export by making the domestic market a lucrative option with limited international competition. Such a shield of protection discourages firms from developing capacity through innovation and R&D, which are critical to being competitive in both the domestic and the international markets.” A range of non-tariff measures (NTMs), including non-automatic licensing, lengthy and complicated registration, and the duplication of inspections in the origin country and Egypt, further undercut the potential for export-oriented private investment.

The fact that a currency depreciation of around 50% in November 2016 only modestly boosted exports indicates that the combination of protectionist trade policies and NTMs are among the structural reasons for Egypt’s weak export competitiveness. Following the 2016 depreciation of the Egyptian pound, exports of goods reached 9.4% of GDP in FY2019, up from 5.6% in FY2016. Yet the share of both goods and services exports in 2019 (17.5% of GDP) remains below the level achieved in 2011 (20.5%). Just three products—oils (not crude), urea, and gold—account for more than half of the increase in exports since 2015. Moreover, these products have relatively limited employment impact and are often supported by distortionary incentives, such as subsidized energy prices.

Productive investment crowded out by the State

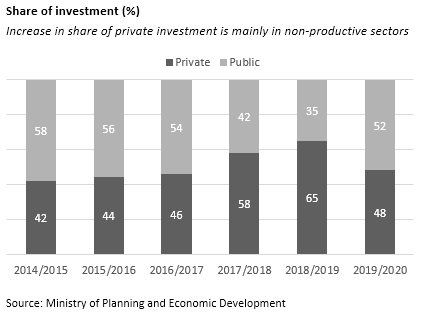

An unfavourable business environment (Egypt ranks 114th of 190 countries in the World Bank’s 2020 Doing Business report) and the large role of the public enterprise sector in the economy also dampens private investment. Despite a recent upward trend, private investment, which reached 9% of GDP in FY 2019, is still considerably lower than in peer countries (15.3% in Jordan, 23% in the Philippines, and 17% in Thailand). Moreover, the increase in private investment’s share of GDP since 2016 comes essentially from the extractive (gas) industries, utilities, and real estate, which have a limited impact on productivity growth.

The flow of private capital to productive sectors of the economy is impeded by private capital being tied up in real estate and high-interest bank deposits. According to a Moody’s report in May, 36% of bank loans were in government securities, while private sector credit as a share of total domestic credit fell from 64.8% in FY 2008 to 32% in FY 2019. The resulting low level of private investment undermines the economy’s ability to absorb Egypt’s almost 800,000 new labour force entrants every year. Most firms in Egypt are microenterprises concentrated in low-skill sectors with 97% of firms employing one to five workers, a share that has declined only slightly over the decade. Meanwhile, the share of medium and large firms has remained stable and extremely low, suggesting that Egyptian firms have difficulty growing. Though Egypt will be among the few economies to avoid contraction this year, growth is driven mainly by private consumption by Egypt’s population of 100 million and government investment spending. According to the OECD, private investment as a proportion of total fixed capital formation has remained at around 10% of GDP since the late 1990s, suggesting that several waves of privatisation, including a renewed push since 2018 to offload public sector firms to private investors, do not provide the answer to Egypt’s weak private investment (except in extractives and construction). The government has rightly prioritised major transportation projects, such as an expansion of the metro system and a new Cairo monorail, as a “locomotive for development,” given that they enhance Egypt’s connectivity and logistics performance. However, unleashing the potential of private investment requires, as the IMF puts it, a “levelling of the playing field” and a phased easing of trade protection measures that is paired with investments in upgrading the digital skills of Egypt’s workforce.