Background and analysis of Egypt’s debt dynamics and how they are likely to play out in the future.

- Heavy borrowing in response to the coronavirus crisis will push up debt servicing costs and dampen the economic recovery

- In the longer term, rising debt and interest payments, the crowding out of the private sector and hard-hit current account receipts will all undermine the economic reform programme

- Egypt’s key sources of foreign currency – tourism, remittances, and the Suez Canal – have all come under pressure as a result of the pandemic and external debt has risen to cover the shortfall

- Reforms to improve the business environment and access to credit will help encourage overseas investment that will be critical to maintaining long-term economic sustainability

- That said, Egypt has performed well through the crisis and is the only MENA economy that the IMF expects to expand this year, mainly thanks to government-backed investment projects

Download the pdf below, or read on for the full report

Key risks linger

Egypt’s favorable market access and sizable Covid-19 stimulus package has allowed it to avoid a sharp contraction and a wider fiscal deficit. However, the pandemic-related debt build-up will add to the already considerable budgetary pressures from interest payments. As with most countries, the course of the pandemic will shape the recovery, but a weaker-than-expected rebound in current-account receipts next year will threaten a return to a downward debt trajectory and undermine the economic reform program.

On 19th November, following a review of Egypt’s 12-month Stand-by Arrangement (SBA) with the IMF (through which Egypt has access to $5.2bn in financing), the IMF stated that Egypt’s economy has performed “better than expected despite the pandemic,” mainly due to the 2016-19 economic reform program implemented under the IMF’s previous $12bn Extended Fund Facility (EFF).

On 21st November, President Abdelfattah El Sisi authorized a new round of stimulus to support the economy through a second wave of Covid-19. The finance minister, Mohamed Maiit, did not specify the size of any fresh stimulus on top of the $2.2bn in unspent funds from the original package of $6.4bn (about 2% of GDP). As Egypt is currently experiencing a modest uptick in Covid-19 cases (with daily new cases about triple the October lows, though still far below the June highs), the funding will likely be used to boost health services and cash transfers to workers in Egypt’s vast informal economy (under the Takaful and Karama social programs).

Egypt is set to be the only economy in the MENA region to expand this year, with the IMF expecting growth of 3.5% in the 2019/20 fiscal year, ending in June, with growth moderating to 2.8% in the 2020/21 fiscal year. This growth is being powered by government-led investment in the hydrocarbon industry, transportation infrastructure and housing projects, offsetting the negative drag from Covid-19.

Egypt emerged from a relatively short (and limited) lockdown in the first week of July, though many constraints had been lifted as early as May. In-bound flights resumed on 1st July, reflecting an urgency to kick-start a recovery in the critical tourism sector, which has been brought to a standstill by the pandemic.

Egypt’s key sources of foreign currency – tourism, remittances, and the Suez Canal – have been pressured by the pandemic. Due to the tourism collapse alone, Egypt is losing $1bn/month in external revenue, while low oil prices have buffeted remittances from Egyptians living in oil-dependent Gulf states and have forced international oil majors to slash capital spending programs related to Egypt’s natural gas resources in the eastern Mediterranean.

Egypt has borrowed heavily in response to the crisis

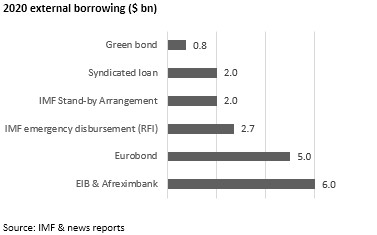

To deal with the financial repercussions of the pandemic, the government has borrowed more than $20bn from multilateral institutions and the international bond market since early 2020. This includes a $2.7bn emergency disbursement from the IMF in May under the Rapid Financing Instrument (RFI) and a $2bn disbursement under the SBA in June. IMF support helped catalyze external private sector financing, including a $5bn Eurobond issuance in May, a $2bn syndicated loan in September and $750m raised in Egypt’s maiden sovereign green bond issuance in September. In July, the European Investment Bank and the African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank) also approved financing facilities worth $6bn for Egypt.

IMF support has underpinned Egypt’s market access by boosting investor confidence, which, coupled with the government’s strong record of reform implementation under the EFF, has been instrumental in avoiding credit ratings downgrades during the Covid-19 crisis. S&P, Moody’s, and Fitch have all affirmed their ratings with stable outlooks, despite pressure on foreign reserves and a collapse in current account receipts. Egypt saw more than $15bn of portfolio outflows in March and April as investors pulled money out of emerging markets (EMs) in a flight to safety.

Reserves declined to $36bn in May from $46bn in February after the Central Bank of Egypt (CBE) stepped in to cover portfolio outflows, debt repayments, and imports of commodities. However, proceeds from external debt-raising have been used to replenish reserves and shore up crisis-related spending. In September, foreign reserves inched upwards for the fourth consecutive month, rising to $38bn, but are still down by 15% year on year (y/y), according to CBE data.

The all-important carry trade

With interest rates in key developed markets reduced to near-zero levels, the chase for yield has led investors back to EMs, including Egypt, which offers one of the world’s most attractive returns on its dollar-denominated debt. Portfolio inflows have recovered strongly, reaching $21.7bn at the end of October, after falling to $10.4bn in May. This has alleviated short-term financing requirements, allowing the CBE to preserve hard-won liquidity buffers. Despite an emergency interest rate cut of 300 basis points (bps) in March and two 50-bps cuts in September and November – in response to low inflation – Egypt’s benchmark deposit rate of 8.75% still offers one of the world’s highest real-interest rates when adjusted for prices. With foreign-currency earnings depressed by the pandemic shock, the CBE will continue to prioritize luring foreign capital to keep currency volatility at a minimum and shore up official reserves.

The CBE’s efforts to boost portfolio inflows have been aided by Egypt’s carry trade, which offers the world’s best return after Argentina. Drawn by yields of around 13% on short-term local debt, foreign bond investors predominantly buy short-term maturity paper, most of it under one year, for carry trades. The risks of dependence on this “hot money” were highlighted in March-April, when the biggest-ever portfolio outflows Egypt has experienced forced the CBE to burn through almost $10bn in foreign reserves to support the Egyptian pound. A continued reliance on hot money, amid a bleak outlook for a recovery in travel and tourism and weaker remittances, exposes Egypt to future shocks related to shifts in investor sentiment. Further, the CBE’s emphasis on maintaining competitive real interest rates for foreign investors has inhibited the use of looser monetary policy as a way of stimulating the economy. The CBE has only modestly and gradually cut rates, despite a contraction in domestic activity in the second and third quarters of the year and a sharp uptick in job losses.

Debt servicing is a strong headwind to the recovery

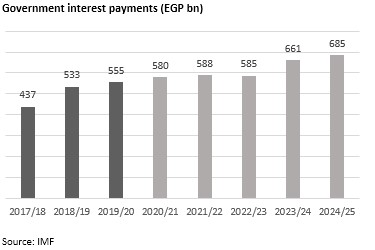

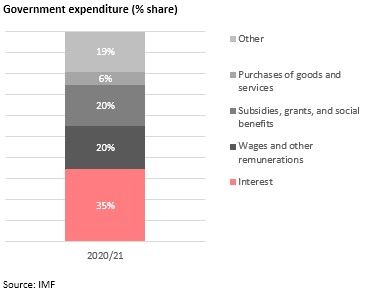

In recent years, the Ministry of Finance has sought to increase external financing as a share of its total borrowing to diminish reliance on the domestic market (especially shorter-term T-bills) and reduce the crowding out of private sector credit given that banks hold more than 50% of general government debt, undercutting growth-enhancing private investment. A shift to external financing is also intended to extend average debt maturity through the issuance of longer-tenor bonds, helping moderate the annual debt servicing burden. The government has managed to increase the average maturity of debt to 3.9 years as of end-June, from about 2 years in fiscal 2016. Yet, Egypt’s debt servicing burden represents a drag on a post-pandemic recovery and on medium-term growth. Interest payments make up the largest single expenditure item in the state budget (more than public sector salaries or subsidies), accounting for almost 10% of GDP. Egypt’s debt affordability (and sustainability) will deteriorate further if a slower-than-expected recovery in revenues forces the government to issue new debt and borrow internationally next year.

External amortizations will require delicate liquidity management

Despite recording small fiscal surpluses since 2018 – mainly due to higher taxes, greater energy independence and the removal of subsidies – a higher interest bill, combined with crisis-related spending, will derail progress on deficit reduction. In addition, higher political risk, related to recurring breakdowns in negotiations with Ethiopia and Sudan over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, compounded by conflict in the Horn of Africa and instability in neighboring Libya, would widen Egypt’s CDS spreads, leading to even higher interest costs. The pressure on Egypt’s credit ratings from the materialization of political risk and pandemic-related fiscal slippage would further increase the cost of borrowing internationally.

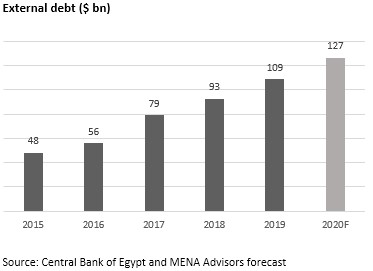

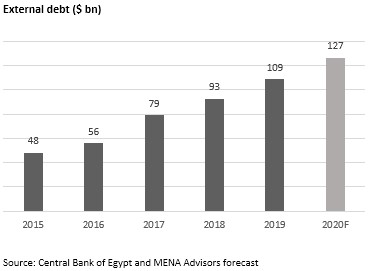

Although Egypt’s external debt/GDP ratio (33.9%) at end-June 2020 was modest by international standards, its external debt stock rose by about 131% in the five years to end-July 2020. By June 2021, general government debt is expected to reach 90% of GDP, from close to 84% in June 2019, reflecting the spike in borrowing triggered by the pandemic’s impact on government finances. This level is above the benchmark of 70% of GDP for EMs. Facing a heavy repayment schedule from 2021, Egypt’s rapid debt-build up, absent a recovery in tourism and foreign direct investment, risks wider deficits in the medium term and even greater financing requirements. However, given that economic growth was on a solid footing and debt was on a downward trajectory prior to the pandemic, an abatement of the Covid-19 crisis should drive a recovery in exports and support Egypt’s capacity to repay its debts.

Egypt must focus on attracting FDI

Egypt’s dependence on portfolio inflows and the attractiveness of its carry trade highlights the urgency of continued implementation of the structural reforms that began under the EFF to improve the investment and business climate. Excessive bureaucracy, regulatory complexity, and the outsized role of state-owned enterprises in the economy inhibit competition and private sector growth. To steadily replenish reserves and lessen the exposure of debt affordability to idiosyncratic shocks, Egypt must look to attract more stable sources of hard currency, especially foreign direct investment (FDI). According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, FDI flows into Egypt increased by 11 per cent to $9bn in 2019, making it the largest FDI recipient in Africa last year. FDI flows were driven by extractive industries related to the development of the massive Zohr gas field, though telecommunication, consumer goods and real estate also attracted investment.

Given historically low prices of natural gas, oil majors operating in Egypt are likely to slash capital spending plans to preserve cash, denting Egypt’s FDI inflows and underlining the importance of creating a more conducive environment for non-oil FDI. In 2017, Egypt passed a new Investment Law, which provides a framework for the government to offer investors more incentives, consolidate investment-related rules, and streamline procedures. Yet, in the World Economic Forum’s 2019 Global Competitiveness Report, Egypt ranks 93rd of 141 countries and 114th of 190 countries in the World Bank’s 2020 Doing Business report, indicating that neglecting structural reforms would imperil recent progress on improving the investment climate. To boost local investment, the CBE should continue to improve access to credit for Egypt’s micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), which are the main source of private sector jobs. Empowering MSMEs will support a jobs recovery and help increase the contribution of the informal sector, which currently accounts for 40% of economic output, to GDP.