Sale of military-owned companies aims to raise cash and encourage private investment.

The move highlights the prominence of Egypt’s new sovereign wealth fund, the evolving role of the military in the economy and the need for cash from overseas.

- In mid-December, Egypt’s government announced that two military-owned companies would be presented for sale to private investors, with the possibility that they could be listed on the stock market.

- The two companies, Safi (which produces mineral water, olive oil and salt) and Wataniya Petroleum (which operates a network of filling stations), are among a portfolio of at least 30 companies under the umbrella of the National Service Products Organisation (NSPO), the economic arm of the Egyptian Ministry of Defence.

- The sales will be promoted by the Sovereign Wealth Fund of Egypt (SFE), which was established in 2018 to take over and commercialise the government’s stakes in sectors ranging from power generation to food processing.

- The SFE has said that the two military-owned subsidiaries have “attracted a lot of investors”, without identifying them, though ADNOC (Abu Dhabi’s national oil company) has reportedly expressed interest in a majority stake in Wataniya Petroleum.

Sales to encourage private investment

The sales are part of a privatisation drive announced by President Abdelfattah el-Sisi in November 2018 and are intended to encourage much sought-after private investment in the economy. Commenting that other military-affiliated companies were in the pipeline, Hala El-Saeed, Egypt’s Planning Minister and chairperson of the SFE, said that the policy is intended to make the private sector the government’s “main partner” in achieving inclusive economic growth.

The IMF has long called on Egypt to prioritise the reform of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), including in an August review of the 12-month Stand-by Arrangement that Egypt has with the IMF (for emergency Covid-19 liquidity support), in which the IMF recommends transparency around the financial performance of SOEs. Despite a privatisation programme that began in the 1990s, the public enterprise sector remains an important part of the economy. SOEs that are loss-making are a drain on the public purse, while those that are profitable can crowd out the private sector and impede the flow of capital to more productive areas of the economy.

New wealth fund forges leading role

The SFE is among a crop of new sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) established by countries that do not have the luxury of commodity-export surpluses to build up a financial ‘war chest’ parallel to central bank reserves. Instead, the SFE’s mandate is integral to the government’s vision for streamlining the SOE sector through the off-loading of state-owned assets, such as farmland or real estate, to the private sector.

In February, the SFE announced plans to help the NSPO market ten of its subsidiaries for private investment. Given the sensitivity around the military’s role in the economy, which has come under local and international scrutiny, the government’s willingness to include military-affiliated firms in its privatisation plans piqued the market’s interest. Military firms operate in an environment of opacity – data on their performance is not available in the public domain – and they enjoy tax-free status and privileged market access, making them an obscure but promising asset class for investors.

In mid-December, following the news around Wataniya and Safi, the SFE’s chief executive, Ayman Soliman, indicated that another three army-held companies would be sold to the private sector in 2021, hinting at a healthy market appetite for stakes in such firms. Bloomberg described the plans as a “potentially historic” pivot to opening part of the economy to private investment.

Role of military in Egypt’s economy

Though the shift is notable, the extent of the military’s embeddedness in the economy should not be overstated. Estimates that the Egyptian Armed Forces (EAF) owns or controls 25, 40, or even 60 percent of the economy are often bandied about, but are based on little data and even less systematic analysis. A thorough review of the EAF’s role in Egypt’s economy by the Carnegie Middle East Center puts the size of the formal military economy at between 1.0-1.5 or 1.5-2.0 percent of Egypt’s (GDP). Taking the upper band of 2% of GDP and a forecast nominal GDP of USD368bn for 2020, this amounts to a roughly USD7bn impact of the EAF on the Egyptian economy.

Privatisation could attract money from overseas

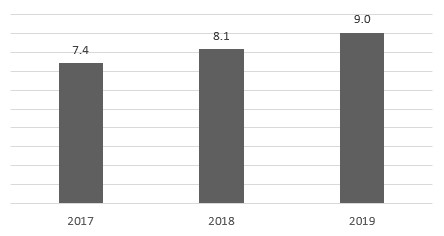

Considering that Egypt’s foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows totalled USD9bn in 2019, the size of the military economy is non-trivial. In keeping with Egypt’s ambition to attract new money into the economy, the SFE’s strategy is to partner with anchor investors (potentially ADNOC in Wataniya’s case) to acquire state-owned assets with a view to future IPOs to a wider investor base. The scope of this plan is not necessarily limited to EAF-owned companies – it may extend to a list of 23 state-owned entities broached by the government in March 2018. Almost half of the companies on offer are in the downstream petroleum and petrochemicals sectors, pointing to the government’s ambitions to move up the hydrocarbons value chain.

Foreign Direct Investment into Egypt ($ bn)

Source: UNCTAD

Egypt needs cash

A renewed focus on privatisation stems from Egypt’s rising gross financing needs, which have increased as a result of pandemic-related spending (Egypt’s general government debt is expected to reach 90% of GDP in 2021). The government views privatisation as a way of creating opportunities for private sector-led growth and attracting FDI. Egypt’s FDI inflows, despite being the highest in Africa, are concentrated in the petroleum sector, which accounted for 74% of inflows in 2019, according to data from the Central Bank of Egypt. Other sectors, such as real estate (7.1%), financial services (2.5%) and communication and information technology (1.3%) accounted for much lower inflows.

The emphasis on FDI and privatisation is likely also motivated by the authorities’ desire to diminish reliance on ‘hot money’ or foreign holdings in local debt (treasury bills and bonds) as a source of liquidity. Between May and mid-October alone, foreign holdings in Egyptian domestic debt reached to USD10.5bn, which is higher than the USD9bn in FDI inflows that Egypt received in 2019. Therefore, the government is using privatisation to diversify FDI inflows away from hydrocarbons and the debt market – while injecting dynamism into the private sector.